|

September 20, 2025 New PERF report on law enforcement–public health collaboration to reduce opioid deaths

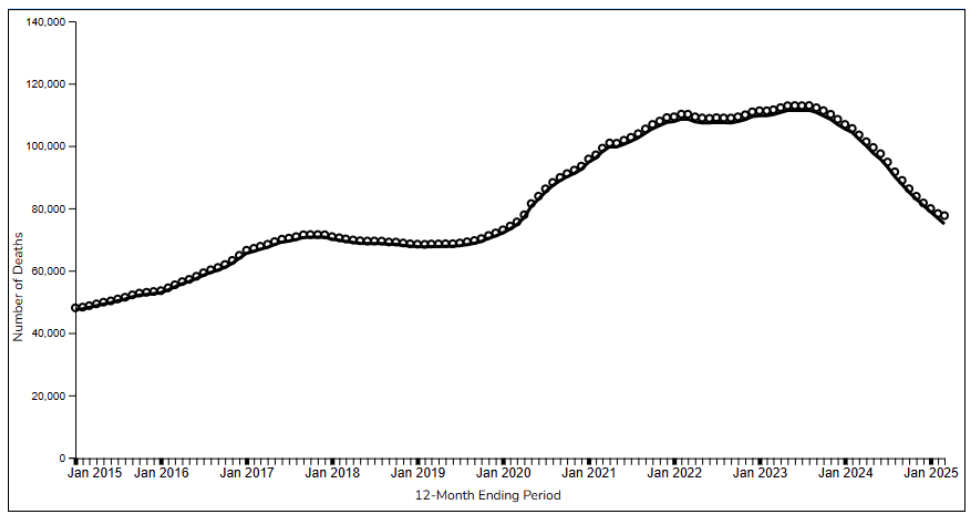

PERF members, The number of drug overdose deaths in the United States rose for decades. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that nearly 111,000 people died from drug overdoses in 2022—more than two and a half times the number of people who died in motor vehicle crashes and about five times the number of homicides. But the CDC also reports that number of overdose deaths has been declining since August 2023. The agency estimates that April 2024–March 2025 saw 25 percent fewer overdose deaths than April 2023–March 2024 (see figure 1). Figure 1.12 month–ending provisional counts of drug overdose deaths in the United States

Of course, we are still losing far too many people to overdoses—more than 75,000 per year. And, as a May CDC statement noted, “overdose remains the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18–44.” But we finally appear to be turning a corner on the opioid crisis. Over the past 11 years, PERF has worked on a series of reports about the opioid crisis. In 2014, we published New Challenges for Police: A Heroin Epidemic and Changing Attitudes Toward Marijuana, which discussed the growing heroin problem and some promising practices for reducing overdoses. Our 2016 Building Successful Partnerships between Law Enforcement and Public Health Agencies to Address Opioid Use report advised public health and law enforcement on how they could better work together.

The following year we published The Unprecedented Opioid Epidemic, which highlighted the dramatic rise in opioid overdose deaths and innovative law enforcement responses to the crisis, such as the use of naloxone and overdose mapping programs. In 2018, we helped bring together a group of public health researchers and law enforcement officials to draft standards of care for police departments as they respond to the opioid crisis. In 2019, PERF and the RAND Corporation produced Law Enforcement Efforts to Fight the Opioid Crisis, which recommended increased use of medication-assisted treatment and closer partnerships between law enforcement, social workers, and others working on these issues. And four years ago we published Policing on the Front Lines of the Opioid Crisis, which detailed police agencies’ three roles in this crisis: emergency response, public safety, and law enforcement.

Today we are building upon our previous work with a new report, Opioid Deaths Fall as Law Enforcement and Public Health Find Common Ground. It summarizes PERF’s research and a meeting PERF co-hosted last year with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, a Distinguished Professor of the Practice at the school. That meeting brought together a cross-section of police and public health officials. Our new report describes the following 11 strategies law enforcement and public health can use to better work together:

Some public health and law enforcement officials have been embracing these strategies for a decade or more. The Quincy (Massachusetts) Police Department, led by Lieutenant Patrick Glynn, began equipping its officers with naloxone 15 years ago. But others have found that the sometimes conflicting priorities of public health and law enforcement can create obstacles to the adoption of these strategies.

Attendees at PERF’s 2024 meeting on opioids review CDC drug overdose data. At our meeting, Philadelphia Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel discussed his city’s Kensington neighborhood, where he said there was an uncoordinated harm reduction approach from 2020 to 2024. “We have these silos of people coming out [to provide services],” Commissioner Bethel said. “No one is creating a true synergy by getting all these folks together in a room and making sure they understand how they all have a value in that space.”

Philadelphia Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel. In 2024, Commissioner Bethel and Mayor Cherelle Parker oversaw a “reset” of their approach to drug issues in the neighborhood. “I believe the reset looks like a combination of my men and women working with our public health personnel to get into that space,” Commissioner Bethel said. “So, when my officers engage a person who wants to go to treatment, they know exactly where to send that person.” And the Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers discussed recent research findings, some of which I shared with you in this column last year. For example, they spoke about the potential for an increase in drug overdoses after law enforcement takes enforcement actions against a drug supplier. As I wrote then, “a study of drug enforcement actions by law enforcement in Marion County, Indiana, found that overdoses increased in the nearby area during the following weeks. This suggests that law enforcement should coordinate with public health officials and service providers to connect drug users with treatment resources when taking enforcement actions against their source of drugs.” We also heard from two mothers whose sons died after consuming fentanyl and who advocate for the use of the term “poisoning” instead of “overdose.” I encourage you to review the report for more details on each of the 11 strategies. It will take a coordinated approach from public safety and public health officials to continue reducing the number of overdose deaths. Despite recent progress, we still lose more Americans to overdose deaths than to homicide, suicide, or traffic crashes. We know neither law enforcement nor public health can solve this problem on its own; collaboration is needed. The strategies and lessons learned in this report can serve as a useful guide for policymakers and practitioners. Thanks to Dr. Sharfstein, who provided invaluable insights throughout the project and generously allowed us to hold the meeting at the Johns Hopkins facility in Washington, D.C. He has spent decades working to prevent overdose deaths and has been a great partner and friend to PERF.

Dr. Joshua Sharfstein. This is the 54th project in PERF’s Critical Issues in Policing series, which is made possible by the ongoing support of the Motorola Solutions Foundation. I’m grateful for everything they’ve done to improve the policing profession. Best, Chuck |